The Faculty of Theology was the most important of the four LEUCOREA faculties. Through the work of numerous reformers such as Martin Luther, Philipp Melanchthon (he held a full professorship at the Faculty of Arts, but also a teaching license for theology), Justus Jonas the Elder, Johannes Bugenhagen or Andreas Bodenstein, the Faculty and the University attained world-historical significance in the 16th century.

According to its statutes of 1508, the faculty awarded the academic degrees baccalaureus biblicus, sententiarius, formatus and licentiatus. A prerequisite for studying at the Faculty of Theology was the study of the Seven Liberal Arts at the Faculty of Art. If a candidate acquired the licentiatus, he or she received a teaching license and was entitled to do a doctorate.

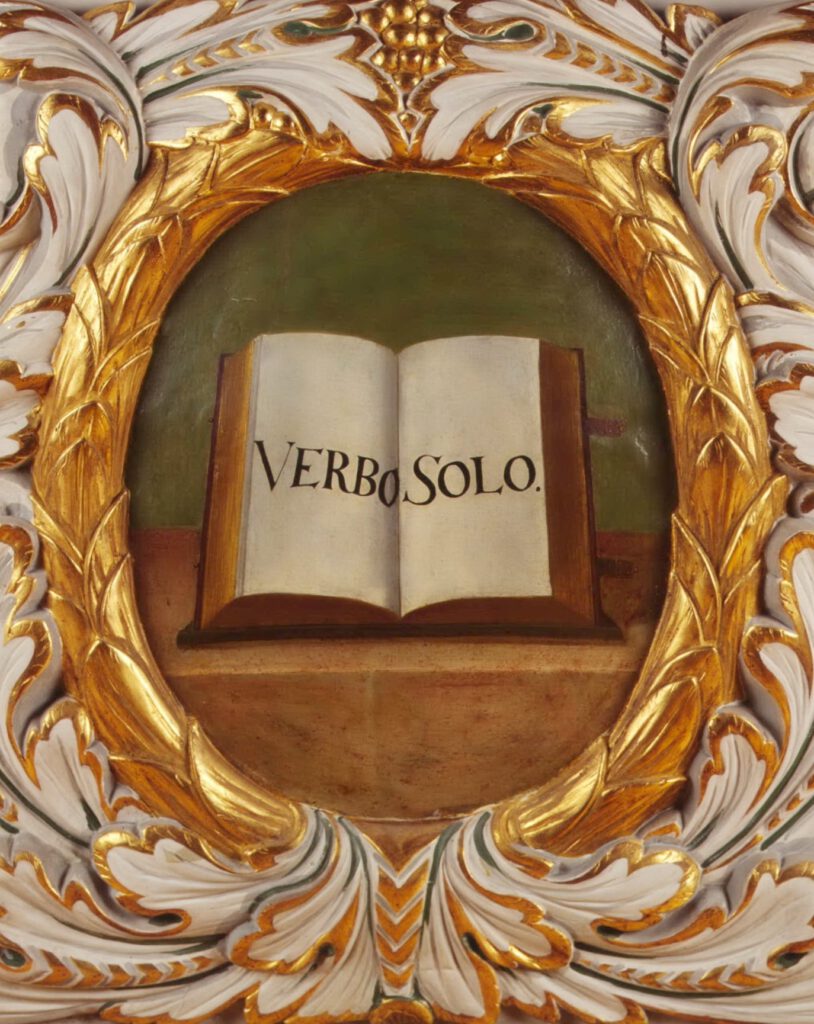

Philipp Melanchthon was responsible for the drafting of new faculty statutes in 1533 and 1545. They were based on the Augsburg Confession and the emphasis on the interpretation of the Bible through philological methods. Of the four full professors of the faculty, two were responsible for the Old and two for the New Testament. Until the end, the faculty had four full professorships, whose teaching duties were changed and adapted over time.

In the early days of the faculty, theological professorships were – as at other universities – connected with religious offices and foundations. At the beginning of the 17th century, the close connection between the activity as priest and university teacher was loosened. While the priesthood had previously been a prerequisite for the professorship, it was now a minimum of three years of study at a theological faculty. The acquisition of the theological doctorate was standardized: Completion of studies at the Faculty of Arts, three-year study at the Theological Faculty, public disputations, three-year service as a pastor.

In the theological interpretation struggle for the implementation of the Reformation, LEUCOREA retained a prominent role in the further course of the 16th century. On the one hand, it became the scene of internal confessional controversies. On the other hand, numerous pamphlets were written against alleged dissenters from „true“ Lutheranism. There were bitter disputes between Gnesiolutherans, Philippists and so-called cryptocalvinists or later with the syncretists.

After the suppression of the cryptocalvinists at the end of the 16th century, the Faculty of Theology became a formative influence for Lutheran Orthodoxy. The teaching of Luther was to be defended in its „purity“ against all the deviations that had been identified. The Wittenberg followers of Lutheran Orthodoxy, with its most important representative Abraham Calov, sometimes attacked their opponents so violently that serious political consequences resulted for the entire university. In 1662, for example, the Brandenburg Elector Friedrich Wilhelm decreed that his subjects were no longer allowed to study theology and philosophy in Wittenberg.

At the end of the 17th century, the conflict with the growing pietism was especially important for the work of Wittenberg’s theological faculty. The Reform University of Halle as the center of Pietism advanced to become the counterpart of the Lutheran LEUCOREA. Against the attractiveness of Pietism and later of the secularly oriented Early Enlightenment, Lutheran Orthodoxy was increasingly in a lost position. This loss of radiance of the Faculty of Theology was accompanied by a decline in the number of students enrolled at the LEUCOREA.